Learn how MAP makes it easy.

TAKE MAP NOWTakes just 5 minutes. Complete the assessment and receive a comprehensive breakdown of your wellbeing across five key metrics.

Step-by-step roadmaps. Discover insights and tools tailored to your personal scores and keep moving toward your goals.

Track and improve. Get happier and grow with proven psychology interventions that strengthen your resilience.

The Science of Your Wellbeing

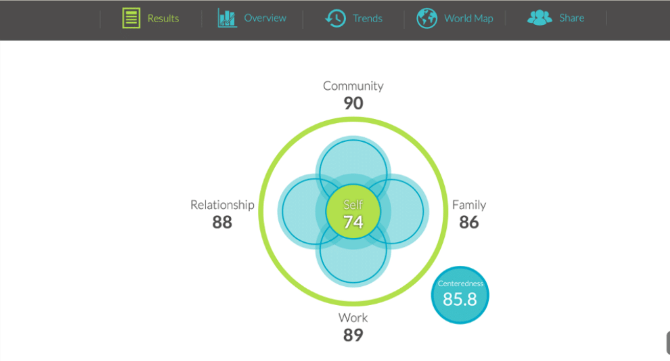

Our scientists have run the numbers. After analyzing thousands of responses from users around the world, we know human wellbeing is made up of five important areas.

In MAP, we call these areas spheres. Your spheres are:

- Community

- Family

- Work

- Relationship

- Self

Community, Family, Work and Relationship represent the four external domains. These domains orbit the fifth domain of Self, which is internal and positioned at the center of the model. The four external domains feed into the internal self and vice versa in a two-way reciprocal flow.

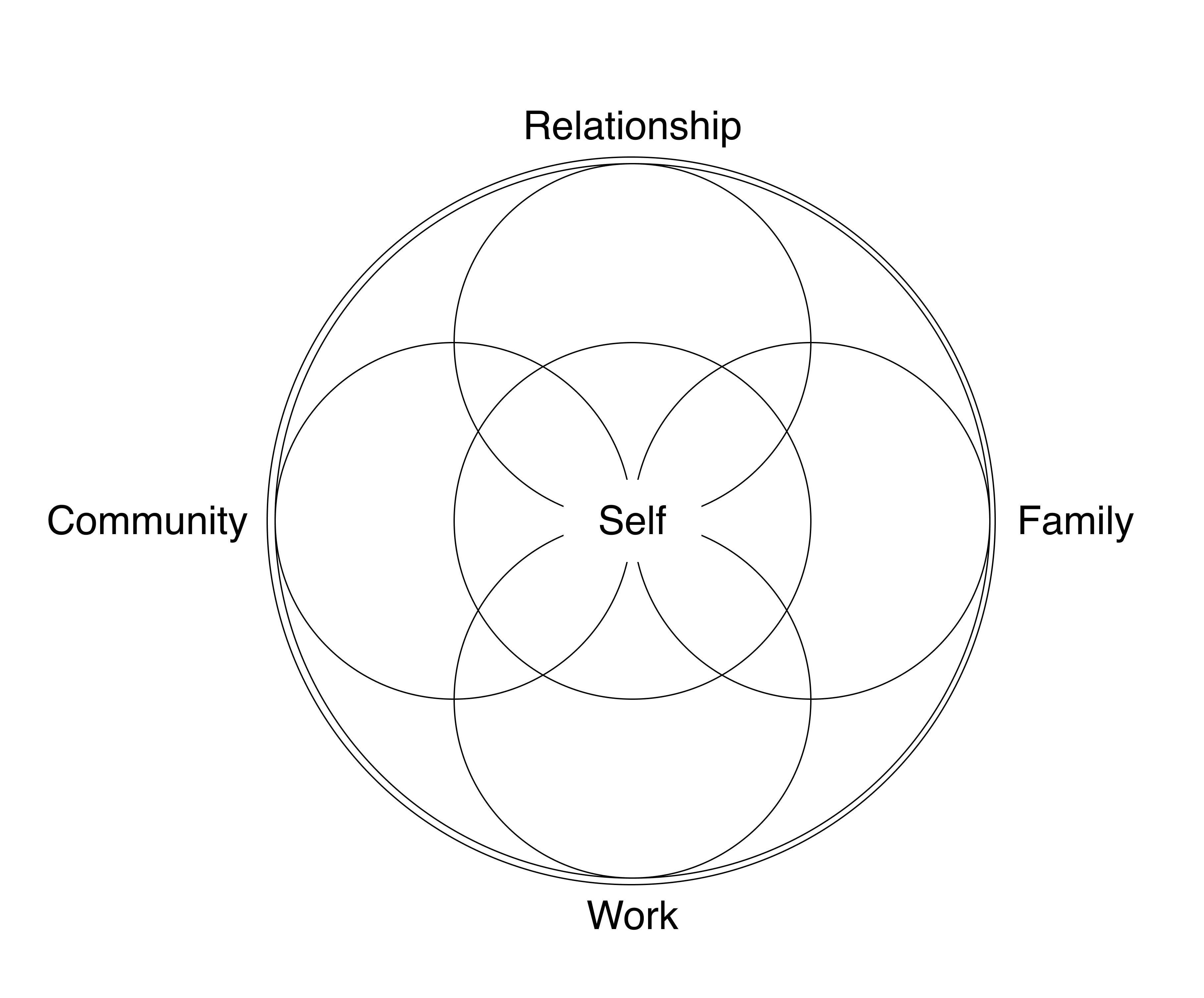

The five spheres of MAP look like this:

The process

- MAP’s algorithms assign a wellbeing score for each sphere. Each score is calculated based on four subfactors within it.

- Greater wellbeing within a sphere means a closer alignment with your ideal life.

- Wellbeing within a sphere influences scores in other spheres. This is why the spheres overlap.

- Algorithms assessing the relative importance of the internal and external domains and their reciprocal impacts gives you a centeredness score—an overall indication of your wellbeing.

When you have a strong and meaningfull vision,

you feel happier and better about your life

Balanced and Centered

You can improve your wellbeing scores in three ways:

Mindfulness Open-minded engagement with the present moment, rather than a narrow view of the past or future.

Positive Goals Goals that lead you closer to the person you want to become, helping you feel empowered and in control.

Positive Emotions Feelings like gratitude, compassion and joy that create an ‘upward spiral’ of wellbeing.

Want to Improve Wellbeing?

MAP tells you exactly where to start.When you take MAP, you’ll receive 20 scores covering the different spheres of your life — Community, Family, Work, Relationship and Self.

You can use these scores to put your effort where it’s needed most.

But where should you start making improvements?

Should you start with your lowest scores? While this may seem like the obvious choice, our algorithms give you smarter suggestions. Using cutting-edge driver tree analysis, MAP’s algorithms do the heavy lifting for you.

We know some scores are more central to your wellbeing than others. MAP accounts for this when making its recommendations.

Your five spheres influence one another. MAP knows how improving one score promises to elevate your wellbeing across others

This means you can often improve several scores at once. MAP highlights these powerful starting points for your wellbeing journey.

Here’s an example…

Imagine you received a lower score on the subdomain of Sensitivity, which is one of four under the sphere of Community. This subdomain is about the consideration you show others in your community.

For example: Are you mindful about how you interact with people in everyday situations, like a train station, or talking to a person in a call center?

To this, MAP may surprise you by suggesting you improve your score on the subdomain of Attentiveness, which falls under the Relationship sphere.

Why could this be?

Our relationships are an opportunity to practice being sensitive to the needs and emotions of another person.

By learning to be more attentive to your partner, your sensitivity to the needs and emotions of others' in your community may grow too, helping you better your wellbeing in two ways at once.

Find YOUR Focus

Based on MAP’s algorithms, you’ll be recommended 4 Focus Areas.

These Focus Areas represent the surest path to a 10% improvement in your overall score, helping you target your wellbeing with precision.

Wellbeing and Happiness

Tested by science, MAP is a compass for YOUR happiness.

If you visualize the CT mandala - like diagram below, and visualize you and your colleague’s mandala interlocking with yours through the work domain, you can see that we are all interconnected and enabled by the connections that we share with others.

We’re all connected. In the same way your scores overlap and affect each other, the scores of others in your life overlap with yours. For example, you share a connection to your colleagues through the Work sphere and a connection to your spouse through the Relationship sphere.

This makes happiness and wellbeing easy to spread.

Your Wellness is an Ecosystem

Happiness is contagious. When you commit to improving your wellbeing, others will feel it across three degrees of separation.

This means that when you increase your wellbeing…

- your colleague will feel it

- so will her husband

- and so will her husband’s social network!

Years ago, Mahatma Gandhi advised that we be the change we want to see in the world.

Growing research suggests science would agree.